“But I was Just Joking!”: The Insurmountable Infringement Defense

November 18, 2022

By David Woodlief, Vol. 21 Staff Writer

“I was just joking!” serves as a less than convincing defense to most accusations. Not so in the Ninth Circuit. There, as Jack Daniels learned in a case it now seeks to bring to the Supreme Court, where an otherwise infringing product “communicates a ‘humorous message’ ” it is almost impossible to win.

Jack Daniels and many commentators fear that the standard “places brand owners at significant risk of infringements and dilutions masquerading as expressive works.” In so doing, they place the value of commerce above the value of expression and do a disservice to the First Amendment.

Is a Squeaky Toy Art?

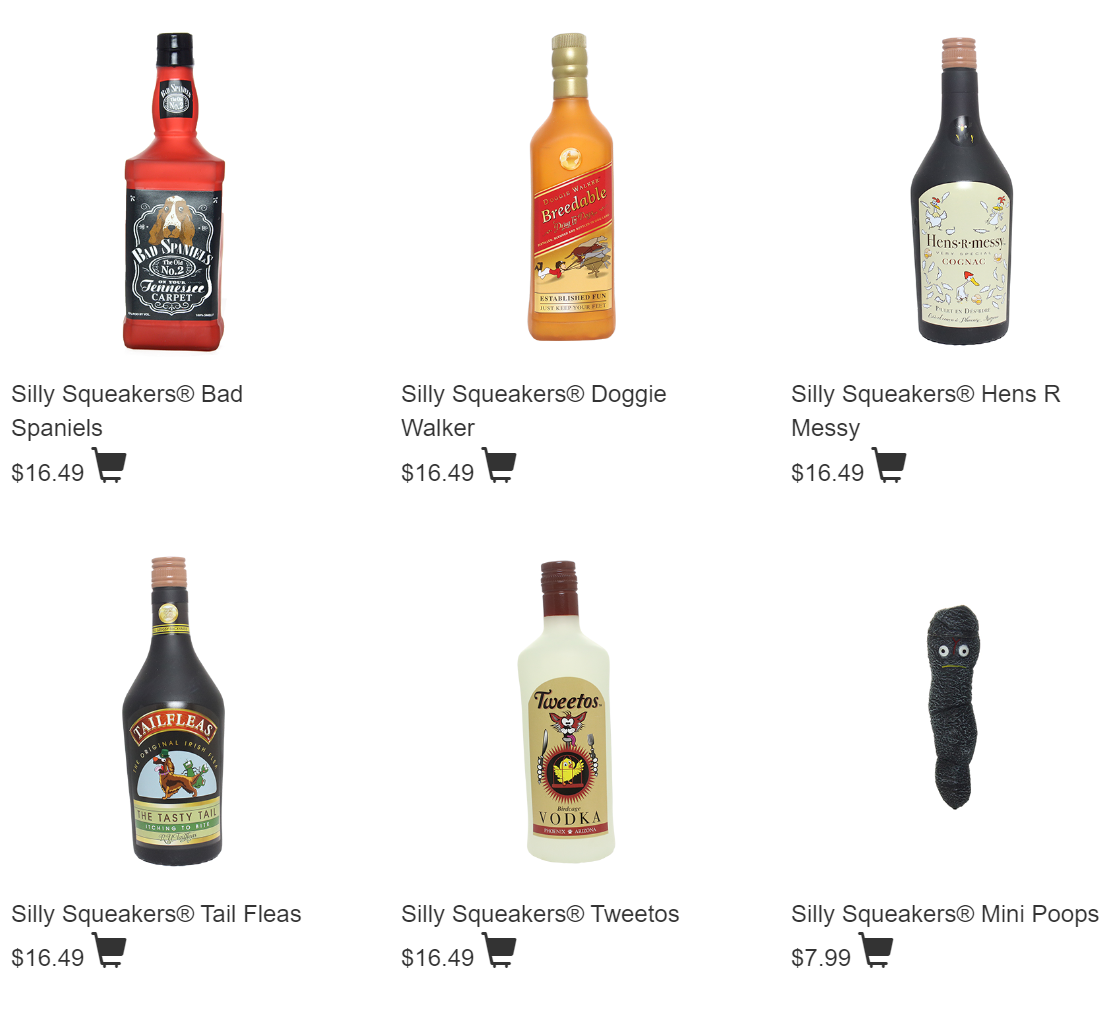

VIP Enterprises, LLC, sells dog toys on its website, mydogtoy.com, including a variety of squeaker toys that parody famous beverage brands. For instance, “Cataroma” associates Corona beer with a cat’s litter-box, and “Mountain Drool” associates Mountain Dew with dog slobber.

Among VIP’s products is “Bad Spaniels,” which mimics the shape and label of Jack Daniel’s signature bottle. Instead of reading “Old No.7 Tennessee Sour Mash Whiskey,” the chew toy purports to contain “The Old No.2 On Your Tennessee Carpet” and to be “43% Poo by Vol.” rather than “40% Alc. By Vol.” Unamused, Jack Daniels demanded that VIP cease use of its protected intellectual property. VIP responded by filing suit in Arizona, preemptively seeking a declaration from the court that its product did not infringe or dilute Jack Daniel’s intellectual property.

VIP argued that Bad Spaniels was a parody and thus an expressive work deserving protection under the First Amendment. Specifically, VIP argued that this was protected speech because it used Jack Daniel’s mark for a purpose “beyond its source identifying function” and not as a part of a commercial transaction. At summary judgment, the court rejected VIP’s argument, finding that parody protections were reserved for more traditionally expressive works like movies, plays, books, and songs. After a four-day bench trial, the court found in favor of Jack Daniels on claims of dilution by tarnishment and trademark and trade dress infringement and enjoined VIP from selling “Bad Spaniels.”

On appeal, the Ninth Circuit saw the humor. Leaving the factual conclusions of the trial court undisturbed, it overturned the decision. It reaffirmed prior holdings that where a work is “expressive,” it deserves special protection. Then, an infringement action can only succeed where the work fails the Rogers test and “is either (1) not artistically relevant to the underlying work or (2) explicitly misleads consumers as to the source or content of the work.”

“Bad Spaniels,” the court said, “juxtapose[es] the irreverent representation of the trademark with the idealized image created by the mark’s owner” and thus “comments humorously on precisely those elements that Jack Daniels seeks to enforce here.” Regarding dilution, the court said that the humorous message of the product places it into the “noncommercial” exception to dilution actions, rather than the parody exception that excludes use “as a designation of source for the person’s own goods or services.”

The Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal and on remand the district court entered judgment in favor of VIP, finding that Jack Daniel’s could not overcome either path available under the Rogers test. The Ninth Circuit affirmed.

Jack Strikes Back

Now, Jack Daniels seeks Supreme Court review a second time. It claims that the Ninth Circuit has created a circuit split and ignored the built-in parody protections within trademark law in favor of protections of its own devise.

In order to establish a trademark infringement action, a plaintiff must prove three elements: (1) the existence of a valid and legally protectable mark, (2) which the plaintiff owns, and (3) that “the defendant’s use of the mark” “causes a likelihood of confusion.” In addition, the circuit courts have long recognized special First Amendment protections in artistic works and titles because they “combin[e] artistic expression and commercial promotion.”

The Second Circuit first used the Rogers test in Rogers v. Grimaldi, because it saw a need for more protection of artistic works and their titles. In that case, the court held that a movie title, “Ginger and Fred,” which clearly connected itself to Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire, did not run afoul of trademark protections because it was artistically relevant to the underlying work and not explicitly misleading.

In other instances, the courts have been less deferential. When dealing with the parodic use of another’s mark for the sale of commercial products, other circuits, including the Second, Fourth, Seventh, and Eighth, provide heightened protection only in that a successful parody weighs against finding a likelihood of confusion. This is the path Jack Daniels proposes.

In order to establish dilution by tarnishment, the plaintiff must demonstrate that “the association arising from the similarity between a mark . . . and a famous mark that harms the reputation of the famous mark,” subject to a few exclusions including noncommercial use and some parodies, those which do not designate the source of the person’s own goods or services.

Bad Spaniels Make Good Law

While the Ninth Circuit’s test may be very permissive, its protection of parody is more in line with First Amendment and fair-use law in other areas than the minor deference argued for.

In Hustler v. Falwell, the Supreme Court held that the First Amendment barred a claim for intentional infliction of emotional distress on the basis of a parody Campari ad lampooning Jerry Falwell. It did so because it believed parody and satire “play[] a prominent role in public and political debate,” where a public figure is the subject. Here, Jack Daniels, who must prove that its mark is famous in order to prevail on its dilution by tarnishment claim, is similarly situated to Jerry Falwell. Like the Campari ad in that case, the parody of Bad Spaniels provides valuable social commentary on a matter of public debate. Though there may be no one proper interpretation of the parody, it provokes the viewer to ask questions about the role that Jack Daniels, other large brands, and alcohol play in society. That it does so in a subtle, humorous, and denigrating way does not deprive it of the same value, contributing to public debate, that parody provides to society.

Against that backdrop, it is hard to understand how a commercial product, like a dog toy, which expresses a message should receive less protection than traditionally expressive works like movies and books receive under the Rogers standard. The justices are considering the case in conference today, November 18, 2022. Should it take up the case, Jack Daniels v. VIP Products would present the Supreme Court with an opportunity to reiterate the value of parody and to cement First Amendment protection throughout the country. It should do so.

***UPDATE*** On November 21, 2022, the Supreme Court granted the certiorari petition and will hear the case!